Hebrew Children’s Literature and the Adult Learner of Hebrew

by Rahel Halabe

Chapter 8a – Level Aleph (Beginners’ level)

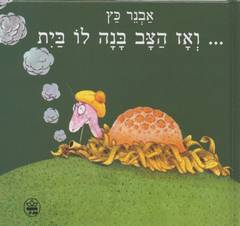

… And then the Turtle Built Himself a House ואז הצב בנה לו בית…

Written and illustrated by Avner Katz. כתב וצייר אבנר כץ

Avner Katz relies on both the visual and verbal to deliver his original story. The shell-less turtles of once upon a time are unhappy. They are looking for someone to build them a house. They find a serious little turtle playing with building blocks. Realizing his potential, they send him to school. When he comes back as an ambitious young architect, he starts building. Each house he builds is stranger than the other. It is only after they are all rejected that he gets his bright idea! Now he is more pragmatic. He measures himself, plans, builds a tiny little house, enters it and stays there. The turtles love the idea. They all follow his example … and live happily ever after.

Much of the story line can be understood without words through the very humorous and colorful cartoon-like illustrations (22 plates). Click on Turtle1 – illustration & Turtle2 – illustration (to see them in small size) and realize their ability to deliver much of the story without language.

The original Hebrew text of this story is much beyond the beginner’s level, for which the prerequisite is reading (deciphering) Hebrew only. The original story uses all tenses, rhymes and mixed registers. Therefore, and in order to adjust it to the beginner’s level, the text was completely rewritten to suit the language objectives of this basic level curriculum. Accordingly it was renamed: הצב בונה בית (The Turtle Builds a House). The illustrations though, were kept intact. The ability of the illustrations to deliver much of the story without language is of course the greatest advantage of this work for the beginner’s level. The illustrations provide the students with a schema with which they can approach both their initial listening to the story and later to their reading. In rewriting the story, there has been a heavy use of the frequent vocabulary and grammar imparted in each of the five course days. Even though the rewritten story gives up many of the original jokes, it manages to comply with the story line as depicted in the illustration. However, due to the many linguistic restrictions (limited vocabulary, use of only present tense and infinitives in verbs, etc.) emphases are different. The rewritten text, using repetitions as well as many additional details in order to impart basic vocabulary and practice recently introduced grammatical subjects, is at times longer. Thus, the 30 word original text of the following 9th illustration (click on Turtle1 – illustration) presented in the third day of the course is replaced by a simpler but much wordier text (100 words). This new text is infused with much of the grammar and frequent vocabulary taught and reviewed up to that point (the 3rd day). The rewritten text uses only simple sentences and verbs in their present tense and infinitive forms. Many phrases and structures are repeated again and again, thus creating a clear pattern and aiding retention. The adapted text practices the numbers,יש /אין sentences, various basic verbs and nouns etc. The following excerpts demonstrate the difference between the original text and the rewritten text attached to the above illustration.

| And after so many years of study, thought and reflection, the turtle returned with a diploma of an excellent home builder. Even a pipe emanating thick smoke was stuck in his mouth. If it won’t help, it certainly won’t harm. |

ואחרי כך וכך שנות לימוד, מחשבה והרהור חזר הצב עם תעודה של בונה בתים מצטיין ואף מקטרת מעלה עשן סמיך תקועה לו בפיו, אם לא תועיל, אז בטח לא תזיק. | Original Text9th illustration |

| He goes to the big city with a small suitcase.He studies many years in the big city.Now he is a young wise turtle.Now he is an architect.He knows [how] to build houses.He builds big houses.Now he comes to the wise turtles with a big suitcase.What is there now in the suitcase?Now there are many clothes in the suitcase. |

Now there are three towels in the suitcase.

In the suitcase there are ten books.

In the suitcase there are eight pencils and nine pens.

In the suitcase there is now a sandwich with arugula.

In the suitcase there is a lot of coffee and tobacco.

In the suitcase there is also a diploma of an architect.

The young turtle says to the wise turtles:

“I am an architect now.

Now I work in architecture.

Now I know [how] to build big houses.”

The wise turtles are happy.

הוא הולך לעיר הגדולה עם מזוודה קטנה.

הוא לומד בעיר הגדולה הרבה שנים.

עכשיו הוא צב צעיר וחכם.

עכשיו הוא ארכיטקט.

הוא יודע לבנות בתים.

הוא בונה בתים גדולים.

עכשיו הוא בא אל הצבים החכמים עם מזוודה גדולה.

מה יש עכשיו במזוודה?

עכשיו יש במזוודה הרבה בגדים.

עכשיו יש במזוודה שלוש מגבות.

במזוודה יש עשרה ספרים.

במזוודה יש שמונה עפרונות ותשעה עטים.

במזוודה יש עכשיו סנדוויץ’ עם ארוגולה.

במזוודה יש הרבה קפה וטבק.

במזוודה יש גם תעודה של ארכיטקט.

הצב הצעיר אומר לצבים החכמים:

“עכשיו אני ארכיטקט.

עכשיו אני עובד בארכיטקטורה.

עכשיו אני יודע לבנות בתים גדולים.”

הצבים החכמים שמחים.

Adapted TextAleph level9thillustration

Katz’s turtle story is supposedly written for children, but it actually addressees adults as well. (see above, chapter 2).[RH1] Its funny story line and wacky illustrations can certainly appeal to both. The adults though, find the satirical depiction of the young architect, his impractical creativity and frustrating pretension doubly humorous. In spite of its being stripped off its intelligent, succinct and playful Hebrew text and replaced by an admittedly lesser text from a literary point of view, the story keeps much of its original qualities, especially its satire. It does so, of course, through its untouched illustrations but also through its animated presentation in class.

After the presentation of the daily passage of the turtle story and its retelling by the students as described in the previous chapter, the conversation moves on in order to apply the language learned. Following the passage, students may talk about their home, belongings, work, other activities etc. Students at this level do not have the tools for ‘discussion’ on interesting more abstract subjects that may arise from such a satirical story, such as their reaction to innovative but impractical inventions and fashions, art as opposed to design, presumption and so on. Still, they may get the satisfaction of grasping these ideas without language, while accepting for the time being the need to practice their limited language skills on pragmatic topics only. By the third day for example, after reading about the pros and cons of the first strange house built by the young turtle (see above illustration no. 11), they can talk about their preferences for their home in simple language: big or small home, big or small kitchen, rooms, windows…, with much light, etc. They can talk about work and study, albeit in the present tense only: where do they work or study? Is their work good, what do they do, how many years do they study or work? They can describe the contents of their bag, purse, backpack or suitcase while traveling: clothes, books, foods, etc. In the fifth and last day they can talk about their leisure activities: do they play games, play music, study, read, exercise, talk with friends, etc? Discussion can be upgraded to more general topics by introducing pictures of practical and impractical inventions and designs. They can express their opinions about different ideas presented to them in pictures: This is a good idea; this is not a good idea. I think that this is a good/interesting idea. I think that this (piece of clothing, utensil, product…) is beautiful, but it is not good/comfortable. I don’t want it. They make nice/interesting clothes, but I think these are not comfortable.

There is one important grammatical subject though, not well covered with this story. The protagonist young turtle and the three wise turtles are all male. The verbs, nouns and adjectives related to them therefore are limited to the masculine and do not provide opportunities to practice the feminine. A possible exercise in which students can try and change the protagonist into a she-turtle and the wise ones into female as well, can correct this. A longer framework than the 25 hour Mini Ulpan can, of course, offer the students a gender balanced variety of stories, not only for grammatical reasons but for the inclusion of both genders.

In spite of the obvious linguistic constraints, the turtle story has been providing beginner students in the Mini Ulpan with an entertaining relief from the pedagogically effective, but poor content conversation, almost unavoidable in the very early stages of L2 learning. They enjoy and appreciate grasping through the illustrations, as well as through their initial Hebrew, the sophisticated satirical points of the story even though they are not able yet to discuss them accordingly. This kind of material helps the adult students overcome the unsettling sense of ‘infantilization’ they may experience at the initial stages of language learning with very limited comprehension and limited ways of expression.

back to: Hebrew Children’s Literature and the Adult Learner of Hebrew , by Rahel Halabe